While the Indian Punjab in general cannot boast of a robust record in the

performance of its social sectors like health care, education, population control

and empowerment of women, the Pakistan Punjab’s record in these sectors has

been much worse, in several instances, poorer than even the most

impoverished areas of the world, says Sultan Shahin.

BOTH India and Pakistan have been moving on the path of economic progress with a reason-

ably high degree of success for developing countries. Unquestionably, the states of Punjab

in the two countries have contributed significantly towards this progress. But economic

growth is not an end in itself and is meaningful only if it brings about social development.

While India in general cannot boast of a robust record in the performance of its social

sectors like health care, education, population control and empowerment of women,

Pakistan’s record in these sectors has been much worse, in several instances poorer than

even the most impoverished nations of the world. Within the two countries, a comparative

study of the states of Punjab further reinforces the fact that economic growth and social

prosperity are completely unrelated aspects of Pakistan’s economy.

Literacy is perhaps the most significant index of social development in a developing country

as all other sectors are dependent on the success in this sector. While the state of education

in Pakistani Punjab is actually poorer than the rest of Pakistan, Indian Punjab has recorded

one of the highest literacy rates in India. The literacy rate in Indian Punjab in 58.5 per cent,

more than double the rate for Pakistani Punjab (24.5 per cent). Male literacy in Indian

Punjab, at 65.7 per cent, is about double the rate in Pakistani Punjab -- 33.5 per cent. In

terms of female literacy, Indian Punjab is almost three-and-a-half times better with 50.4 per

cent compared to Pakistani Punjab’s 14.4 per cent.

More interesting is the urban-rural comparison. Indian Punjab’s urban literacy is 67.1 per

cent to Pakistani Punjab’s 43.1 per cent. Urban male literacy is 72.9 per cent here compared

to 51.5 per cent in the latter, while urban female literacy is 60.3 per cent and 33.2 per cent

respectively. The Indian Punjab also scores over the other in terms of rural literacy. The

average rates for the two are 42.6 per cent and 17.3 per cent. Rural male literacy in Indian

Punjab is 50.5 per cent compared to Pakistani Punjab’s 26.4 per cent. Rural female literacy

in Indian Punjab is 33.5 per cent, almost five times the rural female literacy in Pakistani

Punjab at 7.4 per cent.

More interesting is the urban-rural comparison. Indian Punjab’s urban literacy is 67.1 per

cent to Pakistani Punjab’s 43.1 per cent. Urban male literacy is 72.9 per cent here compared

to 51.5 per cent in the latter, while urban female literacy is 60.3 per cent and 33.2 per cent

respectively. The Indian Punjab also scores over the other in terms of rural literacy. The

average rates for the two are 42.6 per cent and 17.3 per cent. Rural male literacy in Indian

Punjab is 50.5 per cent compared to Pakistani Punjab’s 26.4 per cent. Rural female literacy

in Indian Punjab is 33.5 per cent, almost five times the rural female literacy in Pakistani

Punjab at 7.4 per cent.

Extending the comparisons from state level to the national level, the average literacy rate in

the whole of Pakistan is a poor 35.7 per cent compared to India’s 49.9 per cent. World Bank

figures show that Pakistan’s literacy rate is even lower than that of sub-Saharan Africa

countries like Ghana and Nigeria. School enrolment rates in Pakistan are less than half of

the average in India.

It is also quite futile to talk of a single literacy rate for Pakistan as there are glaring dis-

parities within the country along gender, class and regional lines. Female literacy rates in

Pakistan have remained less than half the male literacy rate since independence, and the

difference has widened over the decades. While male literacy has grown from 17 per cent

to 45.1 per cent between 1951 and 1991, the progress in female literacy has been much

more gradual, from 8.6 per cent to 20.9 per cent in the same period.

The urban-rural bias in literacy rates in Pakistan is even more sharp. The average urban

literacy in Pakistan, according to the latest figures available, is 43.4 per cent compared to

just 14.8 per cent in the rural areas. Urban male literacy of 51.5 per cent is more than

double the rural male literacy of 23.1 per cent. But the biggest gap is between urban and

rural female literacy — 33.7 per cent to just 5.5 per cent. The rural female literacy rate of

5.5 per cent is also the lowest in the world.

Other averages like enrolment and drop-out further underline the dismal state of female

education in Pakistan. The primary school enrolment rate for girls is 15 per cent below the

overall enrolment rate and 8 per cent less than secondary enrolment. Girls moving from

primary to secondary schools in 1987 were 9 per cent less than boys, implying a higher

dropout percentage for girls. A primary factor behind this is lower school availability and

accessibility for girls. Whether or not a school is available in the same or nearby village is

claimed to account for one-third of the large gender gap in schools.

The distance to a school may not be the most critical factor for boys, but for girls, and

especially for those in the rural areas, this makes all the difference between a literate

and a non-literate status.

In a way these distressing literacy rates are not very surprising. Education has never been

a priority issue in Pakistan, as is evident from the extremely low expenditure budgeted for

this sector. It was as low as 1.4 per cent of the GNP in the early 70s, and remained around

1.5 per cent between 1975 and 1985. Since then it has increased to 2.3 per cent, but is

still nowhere near the requirement.

Population growth is perhaps the basic malaise behind all other ills facing both India and

Pakistan. While India has registered an annual growth rate of 2.2 per cent (itself not very

creditable), according to the last census, Pakistan’s growth rate has been as high as three

per cent per annum. This rate has been prevalent since the early ’70s and has led to the

quadrupling of the country’s population from the time of Independence. In fact, the last

census in Pakistan was held in 1981, and if reports in the Pakistani media are to be believed,

the annual growth rate may have neared 3.5 per cent in the last decade. A telling figure

here is that of contraceptive usage, which is just 14 per cent in Pakistan as compared to

43 per cent in India. This is a direct fallout of lack of education.

The reasons for a high growth rate of the population in Pakistan are many. Apart from

extreme poverty and social insecurity, Pakistani society continues to suffer from early

marriage of women and their poor education. Almost 50 per cent of women in Pakistan are

married before the age of 20, enormously increasing the chances of conception. In fact,

the average fertility of women (number of live births per woman) in Pakistan is a high 6.1

compared to India’s 3.7. Another factor is poor education of women. There is abundant

evidence internationally that well-educated women, being career-oriented, generally bear

fewer children. The rate of contraceptive usage is also quite high among educated women.

According to a 1991 survey, only two-fifth of Pakistani women knew of major contraceptives,

and less than a quarter of these actually used them. The reasons cited by them ranged from

the husband preference’s to their cost and even a simple lack of conviction regarding their

usefulness. Also about 30 per cent of college graduates reported using contraceptives, as

compared to 8.5 per cent of uneducated women.

Along with India, Pakistan was one of the earliest countries to recognise the significance of

population control and began formulating measures and policies as early as the 1960s. How-

ever, these policies have undergone frequent changes in the country with changing political

leadership. In the period 1965-73, the population programme relied mainly on the use of

traditional midwives (dais) to motivate the population, distribute contraceptives etc. Zulfiqar

Ali Bhutto’s government in 1973 introduced a mechanism called the ‘continuous motivation

system’, which was meant to be implemented by well-trained couples rather than dais.

The programme suffered a setback in 1977 under the banner of the ‘Islamisation’ programme

of General Zia-ul-Haq, and was discontinued. It was only after 1988, when democratic forces

began to re-emerge in the country that population control measures were restarted. Expendi-

ture on population control has also remained on the lower side in Pakistan, averaging about

0.06 per cent of the GNP.

The health sector in Pakistan defies all logic. Access to health facilities (hospitals, nursing

homes and health centres) is just 55 per cent, as compared to 65 per cent for India. The

average calorie intake in Pakistan measures 2,316 per person per day, while in India it is

2,395 per person per day. The infant mortality rate in Pakistan is 8.8 per cent as compared

to India’s 8.0 per cent. Access to water resources is only 68 per cent in Pakistan, as compared

to India’s 78 per cent.

An interesting fact emerged from a table released by the Government of Pakistan a few years

back listing the main causes of deaths in the country. Almost 64 per cent of the deaths in

Pakistan are caused by infectious parasitic diseases. Diseases like malaria and tuberculosis

account for another 10.5 per cent and 5.5 per cent respectively, taking the toll of all infectious

diseases to 75 per cent, i.e., three-fourth of all

deaths in Pakistan. In rural areas, the situation is worse and it is the infectious diseases that

account for almost 80 per cent of the deaths.

What is the reason for this high incidence of deaths due to infectious diseases? Access to water

resources and sanitation is inadequate in urban areas, and almost non-existent in rural areas.

Resources that are available are unhygienic and contaminated due to the lack of upkeep.

Only around 52 per cent of the country’s population has access to drinking water. While in urban

areas drinking water is available to 80 per cent of the people, it is as low as 45 per cent in rural

areas. Proper sanitation facilities are available to just 22 per cent of the people. In urban areas

the figure is 53 per cent, but in rural areas it is only 10 per cent. In fact, as late as 1985, sani-

tation facilities were absolutely nil in rural Pakistan. It is not a surprise that diseases such as

typhoid, cholera, intestinal infections, malaria, tuberculosis etc have such a high incidence in

the country.

The above figures also reveal a deep-rooted urban bias in the health sector of Pakistan. Even

though 60 per cent of Pakistan lives in rural areas, an overwhelming section of medical personnel

and health facilities are located only in cities. For example, 85 per cent of all practicing doctors

work in the cities, which comes to a doctor-population ratio of 1:1801. The rural doctor-population

ratio happens to be a pathetic 1:25829. Similarly, only 23 per cent of the hospitals in the country

are located in rural areas and only 8,574 hospital beds (18 per cent of the total) for a population

of 80 million.

The health budget in Pakistan is less than 1 per cent of the GNP. Out of this, more than four-fifth

gets allocated to urban-based curative health facilities at the expense of rural health programmes.

An important reason for a lack of trained medical manpower in rural areas is the lack of facilities.

Even if some well-intentioned doctors want to serve in rural areas, the abysmal conditions force

them to change their mind. The government’s approach to the whole issue can be gauged from

the fact that though it ‘urges’ doctors to go to rural areas, it actually pays them less than their

colleagues at equivalent positions in urban health centres.

Even in urban areas the health facilities are largely restricted to use by the upper sections of

society and are beyond the reach of those living in slums and katchi abadis, Pakistan’s rate of

urbanisation is around 4.8 per cent per annum, largely due to migration from rural areas.

Punjab, in fact, has recorded the highest urbanisation rate among all the provinces and today

more than 56 per cent of Pakistan’s total urban population resides in Punjab.

Under the impact of this large-scale migration, slums and katchi abadis constitute a large section,

around 40 per cent nationwide of Pakistan’s urban populace. Health centres and other medical

facilities are non-existent in these settlements. Sanitary provisions and water accessibility are

also practically non existent in several instances, even sewerage and filth-disposal systems have

not been provided. Under such extreme conditions, it is no wonder that three-fourth of the

deaths in the country are caused by infectious diseases.

The low status of women in Pakistani society is already evident from our discussions on population

welfare and education sector. Observations made by Pakistani economist S Akbar Zaidi in Issues

in Pakistan’s Economy provided some further clues:

* Pakistan has the lowest sex rations in the world: in 1985 there were 91 women for every 100

men, down from 93 in 1965.

* According to studies conducted in 1989, Pakistan was one of only four countries in the world

where men lived longer than women.

* Primary school enrolment rates for girls are among the ten lowest in the world.

* While the incidence of ill-health and premature death among the poor of both sexes is very high

in Pakistan, women and girls are the worst affected.

* Pakistan’s maternal mortality rate is the highest in South Asia and great than all other Muslim

countries, essentially due to birth-related problems. This is compounded by the very high prevalence

of babies with low birth-weight — only three countries in the world have a higher percentage of

such babies than Pakistan.

* Only 13 per cent of the labour force is constituted of women, substantially below the 36 per cent

average for all low-income countries.

According to a table released by the Government of Pakistan in 1995, tremendous male-female

disparities persist throughout the country. The percentage of female population is lower than male

population at all age levels: female population is 94 per cent of male population in the age-group

0-14 years, 91 per cent in the age-group 15-49 years, 83 per cent between 50-59 years and just

73 per cent for the group above 60 years.

Female child mortality (1-4 years) is 166 per cent of male child mortality. Just 80 per cent of

females as compared to males undergo full immunisation. On all indices of literacy, female

averages remain only half as high as males. The greatest disparities are evident in the work

force. The number of female professionals is only 18 per cent of male professionals in Pakistan.

At administrative and managerial levels, their employment is just 2 per cent of their male

counterparts.

The discrimination meted out to women in Pakistani society has wide-ranging implications for

the country as a whole. As economist Giovanni Cornia observes in Tariq Banuri’s Just

Adjustment: Protecting the Vulnerable and Promoting Growth, the unsatisfactory social and

economic development record in Pakistan depends to a very large extent on the low status

of women in society, on their low level of literacy, on their restricted access to basic services,

and on a pervasive gender bias in the access to economic resources which is the source of a

severe inter-sex and intra-house hold income inequality.

Source: http://www.tribuneindia.com/2000/20000514/spectrum/main1.htm

KC Singh

Old rulers, new challenges

Rajmata Mohinder Kaur has passed on to her son, Capt Amarinder Singh, a part of the republican and Akali tradition

KC Singh

TWO events affecting the chief ministers in the two Punjabs on the opposite side of the Indo-

Pakistan border remind one of William Wordsworth’s The Solitary Reaper: “For old, unhappy, far-

off things; And battles long ago”. One was the passing away of the Punjab Chief Minister, Capt

Amarinder Singh's mother and the last recognised Maharani of Patiala, Rajmata Mohinder Kaur

nee Mehtab Kaur. The other is Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s ouster in Pakistan on the vacuous

ground of his conduct lacking “ameen” and “sadiq”, words implying undefined piety, inserted in

the Pakistani constitution by the late President Zia-ul-Haq from Islamic jurisprudence, simply

because he concealed the unpaid chairmanship of a free trade zone company in Dubai. Nawaz

is likely to be replaced by his brother, Shahbaz Sharif, the current Chief Minister of Pakistani

Punjab. Both events have provenance that merits recalling.

The Rajmata was married at 16 and became the Maharani of Patiala a year later, on the death

of her colourful father-in-law, Maharaja Bhupinder Singh. She has now left amidst all the pomp

that the mother of the current ruler of Punjab, not just Patiala, automatically begets. Both my

family and that of my wife flourished under the last two rulers of the Patiala state. My wife's

grandfather, Lt-Gen Balwant Singh, rose to head the Patiala state forces before retiring in 1948.

My grandfather, Capt Waryam Singh, was In-charge of Deodi i.e. comptroller of household in

the 1920s, serving a young Bhupinder Singh.

My debt to Patiala is thus indirect and distant, although the past, bits of which one learnt in one’s

youth, is worth recalling. This is also a way of condoling for those who are neither friends of

Captain Sahib nor courtiers, and yet are more than passing acquaintances; protocol and inacces-

sibility rule out a personal visit. The first wife of Maharaja Yadavindra Singh was Rajkumari Hem

Prabha Devi of Saraikela, now in Orissa, from the family of Singhdeos. She passed away unhe-

ralded in 2014, aged 101. The stated reason for the Crown Prince remarrying was the first

marriage being issueless. Actually the truth is more complex.

Alongside the freedom movement agitation began in states run by local rulers for greater political

rights and civil liberties. The Panjab Riyasti Praja Mandal was formed in 1928, aligning itself with

the national All India States People’s Conference. The initiative in Punjab came from Akali workers,

self-confident after succeeding at gurdwara reform. At their first meeting at Mansa on July 17,

1928, they appointed Seva Singh Thikrivala as president. In 1929 they produced a report titled

“Indictment of Patiala” against Maharaja Bhupinder Singh and sent it to the Viceroy. Despite this

the Maharaja, as the sitting Chancellor of the Chamber of Princes was the sole representative of

rulers at the Round Table Conference in November 1930. The Praja Mandal stepped up the

agitation and Thikrivala, who had been once released, was jailed again in 1933, where he died

in 1935.

The father of the Rajamata, Harchand Singh Jaijee, was a close aide of Thikrivala. That is why

despite the family belonging to Patiala, the Rajmata was born at Ludhiana, a part of British India

and out of Maharaja Patiala's reach. In 1936 Patiala state signed an agreement with Akali leader

Master Tara Singh, splitting the Praja Mandal movement. The marriage of Sardar Jaijee’s daughter

to the heir apparent Yadavindra Singh in 1938 thus tied into this appeasing of Sikh sentiments.

In fact, stories circulated that Akali leaders wanted the future ruler of Patiala to marry in a Sikh

family so as to beget genuine Sikh heirs. Ironically, having got their wish in the birth of Capt

Amarinder Singh, Akalis now discover that he has become their main Congress challenger in

Punjab, as the Bluestar taint does not stick on him.

Thus Captain Singh inherited both a regal lineage through his father but also a republican and

Akali tradition through his mother. As an inheritor of this fusion it was not surprising he walked

away from the Congress in 1984 over the Army entering the Golden Temple during Operation

Bluestar. I remember as Deputy Secretary to President Zail Singh in 1984, when PM Indira

Gandhi's office was desperately trying to locate and dissuade Captain Sahib the argument in

Rashtrapati Bhavan was that his maternal Jaijee family had incited Captain Singh. The Rajmata

herself showed the same streak when throwing her lot with the Morarji Desai Congress, due to

her rumoured friendship with Asoka Mehta, one of the founders of the trade union movement

and INTUC. Thus the Rajmata's death closes this chapter of Indian and Punjab history where

she bridged the divide between effete royalty and Sikh and republican traditions, as indeed the

conflict within the Congress between its past freedom movement camaraderie and subservience

to one family.

In Pakistan it is again a concerted attempt by the military and its allies like Imran Khan to end

Nawaz Sharif's attempt to perpetuate family rule. Shahbaz, I have on authority of a former aide

to the then PM Nawaz Sharif, was in the PM's house in 1999 when Nawaz decided to sack the

Army chief, Gen Perevz Musharraf, during an official visit to Sri Lanka. General Musharraf indirectly

confirmed this recently saying he thought Shahbaz was his friend. Nawaz’s family had convinced

him that Shahbaz and Musharraf were plotting against him. So he never consulted his own brother

before his foolish move. Shahbaz is obviously more acceptable to the military than Nawaz's daughter,

Mariam, who was the designated heir. He also has had working relations with Jehadi outfits, having

used the carrot and the stick to control them in Punjab. There will be continuity and change, the

nature of which will determine Indo-Pak relations.

Similarly, the Modi government is not only impaling Lalu Yadav but his entire line of heirs with money

laundering charges. Corruption, money-laundering, Panama Papers, benami deals are the new

weapons which those in power in the subcontinent are using to corner political rivals and their

families. But like the Akalis in Punjab, the BJP may find that clearing the cluttered Opposition leader-

ship stable may actually open space for new leaders who could become the real challenge. The BJP

and the Pakistani Army must remember the Chinese curse: “May all your wishes come true”.

The writer is a former Secretary, Ministry of External Affairs

Source: http:The Tribune://www.tribuneindia.com/news/comment/tales-from-two-punjabs/446088.html

By Rasul Bakhsh Rais

The writer is a security and political analyst and works at the Institute of Strategic Studies, Islamabad

A very tiny minority in India or Pakistan would oppose the coming together of these two countries

after the conflict and climate of hostility that has persisted for decades. I may be wrong, but this is

my reading of popular attitudes in both the countries. The most important thing to study and reflect

on is how the people of Indian and Pakistani Punjab think about the future. It is no longer important

to think about the past — that is gone and is better buried in the dust of history.

There are many divergent views on how India and Pakistan can achieve peace, harmony and establish

true friendship and become economically integrated. The question is, where to start? The simple

answer is economic openness; full, complete, total and unhindered on both sides. The objective must

be to recreate an India-Pakistan market system that existed around the time of our independence.

Some may rightly argue that too much water has passed under the bridge, times have changed and

we are not the same economies that we were once. This, in my view, is more reason for Pakistan to

seek economic partnership with India than with other neighbouring countries. We can perhaps,

progress more by integrating our economy with India’s perhaps more than we can by seeking close

economic cooperation with China. Our geography and location is such that we don’t need to move

in one direction; rather, we can and should look towards India as much as we do towards China.

What about our national security and our problems and disputes with India? There is a counter-

question in my mind. By not opening up our market for Indian goods and reciprocally not getting

access to the Indian market — the market of the second largest and one of the fastest growing

economies — would those problems be solved? Trade and economic openness is in our interest.

The logic of trade and regional integration is that all benefit from it. Every developing country that

has made transitions in economic development has done so by regional cooperation using a

framework of a regional organisation like the EU and ASEAN. Pakistan cannot do it differently.

In terms of popular perceptions and thinking about the future of our relationship with India, there

is a big change in Pakistani Punjab, the largest province of the country. Historically, anti-India

sentiments have been pretty strong here owing to much communal violence during Partition, the

Kashmir dispute and the wars with India. The Punjab mood at the popular level is no longer

hostile towards India. There is also a big change in perception on the other side of the border.

In my view, language, culture and history, if the narratives are right and rational, can unite

communities more than religion. Religion can be as divisive and conflictive as it can be a force for

harmony but that would depend where and in which age and time we live in.

Punjab, across the divided line, has a rich culture, a long history and a common language and

folklore. I share the view that the two Punjabs can bring India and Pakistan much closer and that

too very quickly. How can this be done? There is a great script in the joint communique, the first

ever between any Indian state and a Pakistani province for a brave future. The bottomline is

openness — students, interns, academics, intellectuals getting into the research institutes and

universities of each Punjab. There is so much we can learn from each other’s experiences in the

wider areas of agricultural research, from land and water management to dairy farming.

Tailpiece: Much will depend on pragmatism defeating dogmatism and burying the ghosts of history.

Published in The Express Tribune, December 17th, 2013.

Indo-Pak detente?

Tridivesh Singh Maini

It is important for both countries to think outside the box and create constituencies of peace outside New Delhi and

Islamabad, especially in the two Punjabs

The meeting between Dr Manmohan Singh and his Pakistani counterpart on the sidelines of the

India-Pakistan cricket world cup semi-final at Mohali has provided the much needed fillip to the

relationship between the two countries that was adversely affected by the Mumbai attacks.

While India won both the semi-final and the cup, it would not be out of place to say that in the

context of diplomacy, neither country has lost. Fortunately, Dr Manmohan Singh’s invitation and

Yousuf Raza Gilani’s visit were welcomed in India by large sections of the media and leaders from

across the political spectrum. But Bharat Bhushan, the editor of The Mail Today, expressed

skepticism in an article titled ‘India-Pakistan peace initiative: Mohali spirit seems spurious’, and

dismissed the initiative as a meaningless exercise.

There was only so much that the two prime ministers could have discussed on the sidelines of

an exciting cricket match. The emphasis was rightly on reconciliation and engagement. Dr. Singh’s

remark that Mian Mir, a forefather of Gilani, had laid the foundation of the Golden Temple is a

perfect illustration of that.

The match was played on the Indian side of Punjab, and it is tough to ignore the Punjab-Punjab

dimension. Indian Foreign Secretary Nirupama Rao has said more Punjab-Punjab interactions

were definitely on the agenda.

While Indian Punjab Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal and former chief minister Captain Amarinder

Singh attended the dinner hosted for Gilani, it was disappointing to see Pakistani Punjab Chief

Minister Shahbaz Sharif missing from the Pakistani entourage. The reason for this may be purely

political, as Sharif belongs to the PML-N. But his absence signalled non-realization of the role Punjab

can play in bridging the gulf between the two countries.

The previous regimes in both the Punjabs played a crucial role in easing things out between the two

neighbours. The Punjab-Punjab engagement reached its zenith during the previous Amarinder Singh

regime on the Indian side and the Pervaiz Elahi regime on the Pakistani side. Many of their initiatives,

such as running buses between Amritsar and Nankana Sahib, and cultural and sports exchanges

between the two provinces, have done their bit in improving the relationship between not only the

two provinces, but also the two countries. As a result of this engagement, Captain Amarinder Singh

gained immense goodwill, and he listed the engagement with Pakistani Punjab as one of his govern-

ment’s achievements.

It would also be crucial to mention that current Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal was part of former

prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s delegation to Lahore in 1999.

Both New Delhi and Islamabad need to pay more attention to the relevance of the interaction between

ordinary Punjabis. New Delhi must not lose sight of the fact that Punjab in Pakistan shapes national

perceptions, as it is the dominant force in almost every sphere. Islamabad needs to realise that while

there is a pan-Indian constituency for peace between India and Pakistan, the Indian Punjab’s desire

for peace is the greatest – because the benefits of a harmonious relationship or the ramifications of

an acrimonious one would be felt the most by Indian Punjab.

It is important for both countries to think outside the box – like Dr. Singh did by inviting the Pakistani

leadership – and create constituencies of peace outside New Delhi and Islamabad. Engagement

between provinces, especially the two Punjabs, needs to be encouraged.

Even civil society groups need to stop pontificating in five star hotels of New Delhi, Mumbai, Lahore

and Karachi and percolate down to the lowest level. Initiatives such as ‘Aman Ki Asha’ which restrict

themselves to academics, policy makers and journalists from the elite, should seek to build constitu-

encies of peace in smaller towns.

While Punjabi tarka can not be the core of India-Pakistan relations, it must not be overlooked either,

because of the historical commonalities between the two provinces and their high economic stakes

in a good relationship.

Tridivesh Singh Maini is an Associate Fellow with the Observer Research Foundation. These are his personal views

Source:The Friday Times,Lahore, April 8-14, 2011 - Vol. XXIII, No. 8

Source:

http://www.thefridaytimes.com/08042011/page8c.shtml

A.G. Noorani

The writer is an author and a lawyer based in Mumbai.

LAST month, the government of Indian Punjab asked the central government to negotiate with

Pakistan to allow the transportation of exports through Pakistan’s land routes. It said this would also

improve India’s trade with the Commonwealth of States countries.

What is far more significant is that Punjab also wants the centre to invite it to future trade meetings

with Pakistan. The centre conceded that this issue would be taken up when trade and economic

cooperation are next discussed following a resumption of dialogue.

Fortunately, Amrinder Singh has returned to power as chief minister of Punjab. In his previous tenure,

he gave ample evidence of a commitment to good relations with Pakistan. Not very long ago, the

chief ministers of both Punjabs met to discuss matters of common interest.

Foreign affairs is a subject of the union under India’s constitution and, indeed, of all countries. But

there has been a significant shift towards giving the states some voice on the conduct of foreign

affairs, especially on matters that directly impinge on their interests and their people’s feelings.

The centre needs to loosen its grip on the states’ affairs.

But Article 253 of the constitution enables the centre to ride roughshod on the states’ rights when it

implements not only a treaty but also a decision at an international conference. It states: “Notwith-

standing anything in the foregoing provisions of this chapter [on centre-state relations in the legisl-

ative sphere], Parliament has power to make any law for the whole or any part of the territory of

India for implementing any treaty, agreement or convention with any other country or countries or

any decision made at any international conference, association or other body.” If the government

concludes an international convention on, say, health, parliament will have the power to make any

law to implement it, despite the fact that the subject falls in the state list.

In the last nearly 70 years, the number of such international ‘bodies’ has grown significantly. Article

253 will cover an international sports ‘body’ too. But the political realities since have also altered

radically. From 1990 to 2014, India’s central government was propped up by regional parties. Political

realities affected the play of Article 253 in another respect as well.

Even when Rajiv Gandhi commanded a massive majority in the Lok Sabha, his policy on Sri Lanka

was hostage to the wishes of the Tamil Nadu government. It was the West Bengal’s chief minister

Jyoti Basu’s trip to Dhaka that enabled India to settle the dispute on the sharing of the waters of

the Ganges with Bangladesh. His stature ensured acceptance of the agreement in his own state

while also persuading the leaders of Bangladesh to cooperate.

In June 1948, the Indian government offered the nizam of Hyderabad a draft ‘heads of agreement’

on defence, foreign affairs and communications, which were reserved for the Indian government.

Paragraph 7 added a qualification: “Hyderabad will, however, have freedom to establish trade

agencies in order to build up commercial, fiscal, and economic relations with other countries; but

these agencies will work under the general supervision of, and in the closest cooperation with the

Government of India. Hyderabad will not have any political relations with any country.” If that

was appropriate for Hyderabad in 1948, it is even more so for the states of India’s union in 2017.

It is not necessary to amend the constitution to confer on the states a consultative status on foreign

affairs when their own interests are directly involved. Procedures can be devised by the centre in

consultation with the states and the document can be endorsed by a joint resolution of both houses

of parliament. There is a precedent for this.

In the wake of the constitutional crisis that engulfed Australia when governor-general Sir John Kerr

dismissed prime minister Gough Whitlam from office in 1976, a series of constitutional conventions

were held on a wide range of subjects, including Canberra’s treaty-power. In May 1996, in a detailed

statement to parliament, then foreign minister Alexander Downer announced the government’s

decision on parliamentary scrutiny of treaties and consultation with the states. Treaties will, as a rule,

be tabled in parliament “at least 15 sitting days before the government takes binding action”. Simul-

taneously, a ‘national interest analysis’ would also be tabled to set out reasons for ratifying the treaty.

Two new bodies would be set up: a joint parliamentary committee on treaties and a ‘treaties council’,

which had been rejected earlier.

An agreed parliamentary resolution can give the states greater say on foreign affairs when their

interests are involved and also recognise the right of the chief minister to engage with foreign govern-

ments on economic affairs, provided that the centre is kept in the picture. They do that already —

but the practice should receive formal recognition.

The writer is an author and a lawyer based in Mumbai.

Published in Dawn, March 18th, 2017

The movie reveals how some nuance-killing, uniform traits of the market-driven new world can help us create a

saleable, romantic idea of the old world. Sounds harsh?

Aarish Chhabra

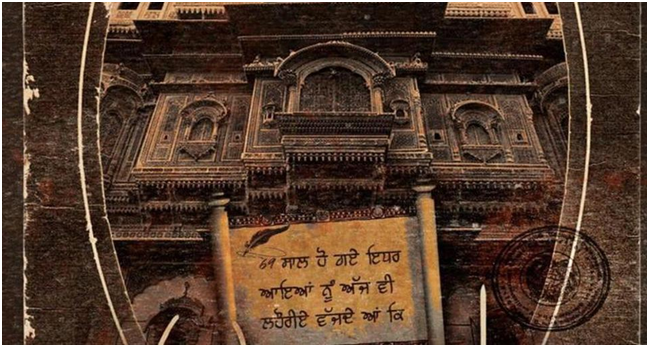

Poster of the movie Lahoriye

How are you supposed to feel when a hall full of people applauds every dialogue about how

the two Punjabs — one in India, the other across a barbed wire, in Pakistan — are essentially

the same? Are you supposed to whistle too? It’s not such an existential question unless you

consider that we live in an age of love measured by hatred. How about we look at things from

this perspective: You are watching the movie in Chandigarh, which won’t have existed had

there been no partition and had Lahore not been sent off to the other side.

This Punjabi movie that carries these anti-national dialogues is Lahoriye, referring to the

people of Lahore. It’s romantic to a fault, and makes everything look so easy and breezy. I

watched it because I wanted to indulge in some sentimental crying in times of sinister laughter

that wants us to laugh along.

Writer-director Amberdeep Singh (Photo: Facebook)

Before you go away thinking it’s all about how I felt, let me discuss a bit of the story for your

benefit. A guy on this side cultivates land right on the border, and so does his eventual love

interest, on the other side. The eventuality does not take long as the romance, like I said, is

easy and breezy. Their eyes meet, and that’s quite enough. Love blossoms with a letter thrown

across the dreaded line, and an easy-visa visit for the hero to her village. It’s all white so far,

very little black. But then, true to his style, writer-director Amberdeep Singh brings in a charming

shade of grey.

The heroine’s cousin is a burly guy, almost stereotypical, who surprises you with how cool he is

about the whole thing. He helps the hero get a rendezvous with the heroine, and love gets

reciprocated. It won’t be a spoiler if I tell you that they eventually get married. It has got all

the ingredients the melodrama, the pretty boy-girl, some fantastic songs.

But it also ends up underlining many other things that perhaps only a Punjabi will claim to know.

It tells you how the third generation after 1947 understands, even feels, a strange attachment

with the mitti, the soil, of our other side. It plays on the language, and shows how a difference

of the Punjabi script — Gurmukhi here, Shahmukhi there — is perhaps the easiest to defeat among

all our differences. And the Roman script of English now unites us, though it was brought to us

by those who divided us. The movie simply tells you how the uniformity of the new world is helping

bring back the old world.

Or, let me reframe that last sentence. The movie reveals how some nuance-killing, uniform traits

of a market-driven new world can help us create a saleable, romantic idea of the old world.

Sounds harsh?

Well, let me be honest. Sometimes, it seems delusional to believe that Pak Punjab must also be

feeling the same affection towards us. I’ve been reminded repeatedly by fellow Indians that West

Punjab has bloodthirsty fanatics running amok, and that the dove-like demeanour of many others

is merely a facade. Those from other states within India even write that sentimentality towards

Pak leaves the Indian Punjabi weak.

I’ve not turned cynical for nothing suddenly. I still don’t have the answer to my moot question:

How am I supposed to feel about the movie? Let me try and answer that for myself: It’s the

same feeling that I felt when I went to Lahore in 2013. It felt odd. So much so that the heart

wants to err on the side of delusion. After all, a delusion that nurtures love is better than a reality

that treats hatred for the other as a mark of love for the own. Define ‘own’.

Source: Hindustan Times, Chandigarh, May 21, 2017

http://www.hindustantimes.com/punjab/two-punjabs-and-an-india-

pak-romance-watching-lahoriye-in-times-of-hatred/story-E1CPoDpAOGXQY49VEF8FxK.html

If only the Kashmir imbroglio would end, India, Pakistan, as well as the two Punjabs would see tremendous growth benefiting

everyone.

MANOHAR SINGH GILL

PHOTO - TRIBHUVAN TIWARI/OUTLOOK

On 18th August, 2014, the University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan decided to confer

on me an Honorary Doctorate for my work in Agriculture and Rural Development, in my

Punjab, as Secretary, Agriculture India, as head of a huge programme of agricultural and

rural development in Sokoto, Nigeria, and for my work and writings on our Punjab's Green

Revolution. I could not go for the convocation and agreed to attend the 22nd Convocation

of the University, on the 26th of March, 2015.

My wife and I, accompanied by Dr. Kaveri Gill crossed Wagah on the 24th of March. We

went over only a few days after the Samba shootings on two separate days. I found little

activity at the Attari integrated check post. There were only 200 trucks, mostly carrying

vegetables. I found a similar number carrying cement and gypsum on the other side. The

trade across the border is somnolent. Inside the elaborate new custom facility, I found many

staff of every kind, and almost no passengers. I was told that at best about a hundred and

fifty go across, and a similar number come over in a day. While we built a broad highway to

the border, there is little economic activity on it, due to a half dead border crossing. On the

other side too, Dograi remains the same, little rambling village, I saw after our unfortunate

fight in 1965. Lahore has not expanded towards the border. The vast border check staff on

both sides is a bored lot, yawning the whole day, and dying to have a passenger come by.

Even the policemen, who stomp about at the evening's fake hostility, lounge about the whole

day. Somehow, all the dialogues, high and low, front end and back channel, are invariably

shadow boxing, bereft of any progress, towards good normal neighbourly relations.

In Lahore, we stayed at the British era Lahore Gymkhana. Funny enough, as a member of the

Viceroy's Delhi Gymkhana, I can check in and stay there, as our mutual rights remain intact,

never mind historical changes! The fact is, as I once said in Parliament, it was not the partition

of India really, it was the Partition of the Punjab, total and brutal, and of Bengal. Even today,

in states distant from Punjab, in the south or the east, people have little idea or interest, in

the horrors of August, 1947 in the Punjab. We on the other hand continue to live that story.

God forbid, if there is ever another fight, we in the Punjab will pay heavily.

The tensions that further developed in 1948, in Jammu and Kashmir, and continue today,

have further impacted the Punjab, adversely. Numerous wars big and small, ensure that the

Punjab remains in a frozen land locked corner. Industry was never encouraged in the Punjab,

the border being the excuse, and now has logically moved away southwards closer to the

ports and transport. Any Punjab products are taken in a circuit to Mumbai — Dubai and onto

Pakistan at a higher profitable earning. The Punjab is bereft of any economic activity. The

adverse result is known to all. If only the Kashmir imbroglio would end, India, Pakistan, as well

as the two Punjabs would see tremendous growth benefiting everyone. Till then, our punishment

continues.

In Lahore, I always visit the Lahore University of Management Sciences. It is an outstanding

school, set up by Syed Baabar Ali, who was a class fellow and friend of Harcharan Singh Brar,

the former Punjab Chief Minister. The students, boys and girls and staff, quizzed me on every

possible curiosity. I have never hesitated to answer. I had tea in the canteen, not in the Vice

Chancellor's office, as I wanted to see how the students mix. I felt as if I was in JNU, with no

gender oppression. In the evening, I saw the same, in the quadrangle with groups in easy,

comfortable discussion.

The next day we travelled to Faisalabad, the Lyallpur of the British. It was the richest canal colony,

heavily pioneered by Sikhs, and with a new well laid out district city, complete with a clock tower.

At the end of March, I saw miles and miles of rich wheat fields. Our people lost them, and got little

land of an inferior quality in the East, while those who went west became "land rich". I heard

stories of people from Jallandhar, bastis, who had little land, grabbing hundreds of acres there.

That is life. They are going to have a bumper harvest in the West, but unlike in the East, there is

no minimum support price, nor any compulsory procurement. The Government will buy some grain,

very likely that too from the Vadheras.

The tenants and the small farmers mostly live in mud villages, which have disappeared in the East.

The big owners all live in Lahore, and spend the summers in London. I noticed that all these small

farmers kept a large number of buffalos for milk. I was told that this milk is sold to Lahore, not

through organised milk cooperatives, or privately owned milk units, but sadly, by milk vendors

carrying brass milk pots on heavily laden motorcycles. I have a dream of visiting Jhang and the

graves of Heer and Ranjha. Sadly, today's Ranjhas are reduced to selling milk on over-laden

motorcycles. This is no way of encouraging a worthwhile milk production industry for the benefit

of the farmers. The Amuls and Punjab Milk Federations Verka butters are unknown there.

The Agriculture University of Faisalabad, was started, as a small B.Sc. college in 1905 by Lord

Curzon. Many of our stalwarts are from there, and the Punjab Agriculture University, Ludhiana

was set up by the migratory staff of 1947. Today, Faisalabad is a comprehensive university,

teaching all subjects, with an impressive campus on 500 acres, and with 20,000 students. What

really struck me was the fact that 10,000 of these are girls, studying everything from agriculture

to physics and chemistry, all the way to Ph.Ds. At the end of March, the University celebrates the

coming of spring. We went around everywhere. Many girls were wearing 'Naqabs', but this did

not surprise me. After all some Sikh girls too wear turbans; Hindu girls sometimes wear saffron

in various ways. One should accept all. The girls, all of them were happy to talk to me. I simply

saw no difference between the Faisalabad University and the Punjab University, Chandigarh. I

just saw vibrant young people pursuing education and interacting freely. In my speeches last

year, and this year, at the University, I expressed my happiness at the large number of girls

pursuing higher education. I stated boldly, that these girls would carry Pakistan, to high levels

of development and progress. I also said cheekily, that the girls would drag the boys too, to

the heights of progress. 3,000 girls sitting there, cheered me on. I suppose they have never

heard such a strong endorsement of their cause. My wife and Dr. Kaveri Gill had a separate

meeting with a hundred odd ladies from the faculty and girl students, where they freely discussed,

the problems of women in this world. They were most interested to know our experiences. Vinnie

and Kaveri explained our ways, in a family of strong willed ladies, and me in a minority of one.

My situation evoked great sympathy.

I gave away a Ph.D to a girl on the subject of water engineering. Later I quipped that we could

use her services more than they. Actually, both Punjabs have water worries and both need a

constant dialogue — between the two universities of Ludhiana and Faisalabad — to learn from

each other, and find solutions to our common problems, of soil, water, water logging, salinity

and many more. I would even urge an exchange of some students and staff for short term visits.

Much will be learned and many closed doors of the mind will be opened.

On the Mall Road we visited the historic museum, where Kipling's father Lockwood worked. It has

a remarkable collection of Buddhist relics, as well as fine miniatures. Kim's Zam Zama Cannon,

actually 'Bhangian Di Tope', the gun last owned by the Bhangi Misl Sardars from Amritsar, stands

in front of the Museum. I visited the Government College, Lahore, which is now a University. The

British Gothic building is undergoing extensive repairs. At the Gymkhana, having breakfast one

morning, I heard an elderly gentleman ordering a 'Pakistani Omelette'. I was surprised and asked

him. He replied "Jee Saade Omelette Vich Rajj Ke Mirchan Paiyan Jandiyan Ne (Our omrlettes are

stuffed with chillies)". I ordered one too. I hope nobody here minds.

• Nostalic feelings of a retired old man about a place left behind is understandable. But his naive

understanding of reality questions how he managed to perform as a senior bureaucrat.

When a group of people chooses to separate from others with almost similar cultural identity in the

name of religion and fosters the communal hatred as justification of their difference there is never

any hope for reconciliation. I also socialize with Pakistanis and Bangladeshis. And we are different

in spite of the similarities.

APR 27, 2015 10:47 PMDC, NEW YORK, UNITED STATES

Source: https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/a-journey-to-the-other-punjab/294109

Posted :Aug 3, 2017

by Rohit :

Indian Punjab vs Pakistan Punjab

Indian Punjab and Pakistan Punjab were part of India before the division of Pakistan from India in

1947. With the partition of British India in 1947 into India and Pakistan, the state that most bore

the effect of division was Punjab. Larger part of Punjab on the western side went to Pakistan and

the remaining to India. The Indian state of Punjab was subsequently divided into smaller states of

Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Haryana. Hindus and Sikhs fled Pakistan for India, while Muslims

sought a home in Pakistan. Today, Punjab Province in Pakistan is 97 percent Muslim and 2 percent

Christian, with small numbers of Hindus and other groups. Sikhs account for 61 percent of the

people in India’s Punjab State, while 37 percent are Hindu, and 1 percent each are Muslim and

Christian. Small numbers of Buddhists, Jains, and other groups are also present. Hindus and Sikh

refugees from west Punjab who migrated to India settled predominantly in the states of Delhi,

Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Jammu & Kashmir and Haryana.

Punjab has been home to many religions. Hinduism florished in Punjab through ancient times,

followed by Buddhism. Followers of Islam held political power in the area for nearly six centuries.

Sikhism has its origins in Punjab, where Sikh states survived until the middle of the twentieth

century. After the British annexed Punjab in the 19th century, they introduced Christianity to the

region. Thus Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, Sikhism, and Christianity are all represented among the

Punjabi people.

In Pakistan, Punjabi is written using the Persian-Arabic script, which was introduced to the region

during the Muslim conquests. Punjabis in India use the devanagri script. Punjabi is spoken by two-

thirds of the population of Pakistan. In India, by contrast, Punjabi is the mother tongue of just

under 3 % of the population. Punjabi was raised to the status of one of India’s official languages

in 1966. However, Punjabi continues to grow and florish in India, whereas in Pakistan, Punjabi

never received any official status and has never been formally taught in schools. Punjabi vocabu-

lary in Pakistan is heavily influenced by urdu, whereas punjabi in India is influenced by Hindi.

Source: http://www.differencebetween.com/difference-between-indian-punjab-and-vs-pakistan-punjab/

• TRIDIVESH SINGH MAINI

New Delhi and Islamabad dominated dialogue have failed to come up with any solution to vexed issues like Kashmir.

May be sub-regions like Punjab and other border provinces like Rajasthan-Sind.

Introduction

During the course of this write-up, the writer seeks to explore an area which has not been researched

enough, both within South Asia, and outside the region; the potential role of Punjabi identity in

narrowing the divide and acting as a bridge between India and Pakistan.

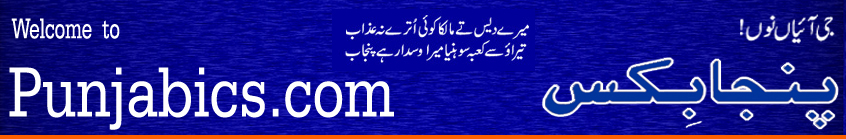

At the outset, it would be important to familiarize all of you with the term "Punjab" and its geographical

location (though I presume, that most, if not all of you would be more than familiar with the Punjab

and its geographical location). The word Punjab, means "Land of the Five Rivers" in Persian. The five

rivers are Sutlej, Beas, Jhelum, Chenab and Ravi. In the pre-1947 epoch, Punjab was an important

geographical unit of South Asia, with Afghanistan to its West, the Central Indian Plateau to its East,

Kashmir to its North and Sindh and Rajasthan to its South.

After the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, the larger part of Punjab went to Pakistan, while a

much smaller portion merged with India. Three rivers (Sutlej, Beas and Ravi) remained with the

Indian side of Punjab while two (Jhelum, Chenab) went to Pakistan. In 1965, the Indian side of Punjab

further got trifurcated into the states of Haryana and Himachal. In the present day, Punjab is a region

that encompasses Northern India and Eastern Pakistan. Punjab is bounded on the north by the vast

Himalayan ranges, which divide it from China, Tibet and Kashmir; on the east by the river Yamuna,

the North-Western Provinces and the Chinese Empire; on the south by Sind, the river Sutlej, which

separates it from Bhawalpur, and Rajputana; and on the west by the Sulaiman range, which divides

it from Baluchistan, and Afghanistan, which joins the Khyber.

Common Identity

Punjabis on both sides also share a common cultural identity, which is referred to as ’Punjabiyat’.

While the spoken language of all Punjabis is Punjabi, folk tales like Heer Ranjha and Sahiba Mirza

considered the sub-continental equivalent of Romeo and Juliet bond all Punjabis. Apart from cultural

commonalities, heroes too are common and actually still remain. Some prominent examples of

common heroes on both sides are Guru Nanak Dev founder of the Sikh faith who is revered by both

Sikhs and Muslims, Waris Shah, Baba Bulle Shah and Baba Farid all Sufi saints respected on both

sides of the border and freedom fighters like Bhagat Singh. In the aftermath of partition, this Punjabi

identity suffered to some degree, because government policies in Pakistani Punjab were unfavorable

towards the Punjabi language and while Punjabis dominated virtually every realm in Pakistan, the

Punjabi identity and Sufi thought was not given much importance.

Change in the Last Few Years: From Battleground to Connector?

It would be only fair to mention here that over the last few years that some policy makers, a handful

of strategic analysts and academics have begun to realize that Punjab on both sides has a pivotal

role to play in acting as a bridge between both the countries, the reasons amongst others are cultural

commonalities, economic interests and most importantly the logic of geography which binds both

the Punjabs.

For a long time after the vivisection of India, Punjab was projected as the flag bearer of conflict.

Firstly, even if both the Punjabs were to forget partition, and the wars which both sides have fought,

the other major roadblock to Punjab playing a positive role in Indo-Pak relations was that while

Indian Punjab was too small and insignificant to influence policy makers at the national level, Pakistani

Punjab had donned the mantle of Pakistani Nationalism, this phenomenon can be attributed to the

complete domination of all political institutions and most importantly the army by Punjab. This point

is very well illustrated by the following statistics:

Punjabis make up 50 percent of Pakistan’s population and constitute a disproportionate percentage

of the army. According to the Brookings Institution’s Stephen P. Cohen, 75 percent of the army comes

from just three districts in Punjab and two bordering districts in the Northwest Frontier Province. The

officer corps, while more urban and diverse, remains disproportionately Punjabi as well.

More than sixty decades after partition, it would not be wrong to say that Punjab on both sides is

emerging as a bridge, rather than battleground, between both countries as interactions have seen

a manifold increase and Punjabis on both sides (especially the Indian side) have begun to realize

that the biggest sufferer of war in economic terms is the Punjab, while the biggest beneficiary of

Indo-Pak peace can be the Punjab.

A good illustration of this point is the fact that despite the two central governments bristling with

hostility, trade at the Wagah border (the main land crossing between both countries, which divides

the two Punjabs) nearly tripled. The total value of exports to Pakistan from the April to October

2008 period, before the Mumbai attack in November, was approximately $23.59 million; during

the same period in 2009, that figure nearly tripled to $66.71.

One other reason for the thaw between the two Punjabs is the common culture. For long, this

aspect of the relationship was overlooked both within South Asia and outside, but of late the

cultural angle has begun to draw some attention. There are a number of reasons for this.

Firstly, people to people contact between the two countries in general and the Punjabs in particular

has seen an increase in the last decade. The organizations which have done yeoman’s service to

enhance interaction between the two Punjabs are the World Punjabi Congress and the South Asian

Free Media Association. Maximum credit for emphasizing the importance of Punjab in the Indo-Pak

relationship goes to civil society organizations like the World Punjabi Congress. Led by a former

Federal Minister, Fakhar Zaman this organization has been advocating easing out of visa-procedures,

opening up trade routes and promotion of a common Punjabi identity. In fact, even the rapport

between the erstwhile Chief Ministers of both the provinces (Captain Amarinder Singh, Indian Punjab

and Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi, Pakistani Punjab) began as a result of a WPC function organized at

Lahore by Zaman in January 2004.

Second, there is a growing realization in the political leadership not only of both Punjabs, but also

at the national level, that interactions will be beneficial. While between 2004 and 2007, the

erstwhile Chief Ministers of both provinces were responsible for pushing cooperation between the

provinces. Off late even prominent national leaders, most notably the former Prime Minister of

Pakistan and head of the Pakistani Muslim League (Nawaz), (PML-N), Nawaz Sharif at a public

speech, in Lahore, spoke about not only a better relationship between India and Pakistan, but also

between the two Punjabs which share a common culture and heritage.

Thirdly, the Punjabi diaspora from both India and Pakistan has played a stellar role in the thaw

between the two Punjabs. Being away from home the diaspora is free from the baggage of the sub-

continent. It is important to note that at an individual level, Pakistani Punjabis and Indian Punjabis

got along extremely well on foreign shores even when there was tension between the two countries.

Back home in the sub-continent, both sides were apprehensive of openly exhibiting any sort of

affinity for the other side. The diaspora has played a very constructive role in encouraging the growth

of "Punjabiat" or a common culture. Alyssa Ayres rightly states that:

The two Punjabs wield disproportionate influence in their respective countries, and they can call upon

a prosperous and culturally active diaspora in the West, which, through the growing popularity of

Punjabi musical and cultural events, has begun to carve out a distinct Punjabi sensibility that transcends

the national divides back "home."

Amongst other initiatives of the diaspora, two stand out. The International Journal of Punjab Studies,

Academy of the Punjab in North America, APNA and The International Journal of Punjab Studies started

in UK was the first which brought together scholars from both the Punjabs and had articles on the

economy, culture and polity of the Punjabs. APNA is amongst the first organizations, to promote Punjabi

Culture over the internet. More recently, it has started a Punjabi magazine called "Lehar" which is

published in both scripts, Gurmukhi (East Punjab) and Shahmukhi (West Punjab).

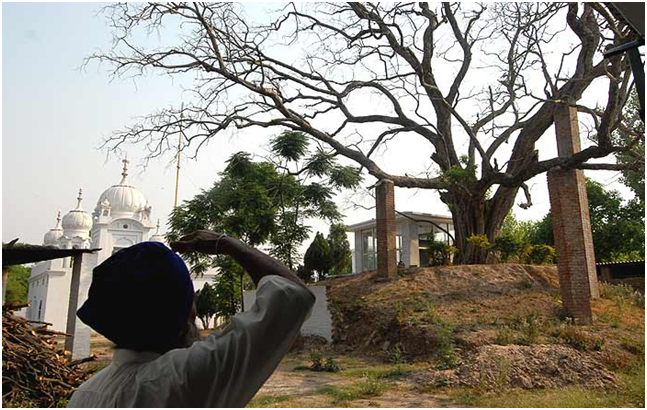

Fourthly, the angle of religious tourism has also played a pivotal role in bringing both Punjab’s closer.

In the last six years, Sikh pilgrims have been paying obeisance at historical religious shrines in Pakistan,

such as Nankana Sahib and Panja Sahib. These pilgrimages have not been disrupted even during times

of tension. Pilgrims, who are apprehensive about visiting Pakistan, return with a different opinion, as

they are warmly received by the Pakistani public. One particular idea for enhancing religious connectivity

between India and Pakistan have been gaining ground. It is the campaign for the Kartarpur corridor. For

those not familiar with the term, Kartarpur (now in Pakistan) is the place where the founder of the Sikh

faith, Guru Nanak, spent the last 18 years of his life and had both Hindu and Muslim followers. Kartarpur,

which falls in district Narowal, is home to the Sikh shrine Darbar Sahib, and this shrine is barely three

kilometres from the Indian border. Before the Indo-Pak war of 1965, it is said that there was a bridge

on the Ravi that Sikh pilgrims could cross over and visit Darbar Sahib. During the 1965 war, however,

this bridge was destroyed; it might be mentioned that the relationship between the two countries

became more tense in the aftermath of this war and visa regimes became stricter with the passage

of time.

For a long time-nearly a decade-Sikhs, predominantly settled in the Indian Punjab, have been demanding

visa-free access to Darbar Sahib. This demand has been accepted by the Pakistan government and is

being looked into by the Indian Government. The demand for the Kartarpur Corridor has been receiving

the support of diaspora Sikhs and The Institute of Multi-Track Diplomacy, a Virginia-based organization

actively engaged in conflict resolution in South Asia and other parts of the world.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there are numerous impediments to Punjab-Punjab interactions, as nation-states determine

these policies and there is only a limited role which a common cultural identity can play in reducing

tensions between countries. But I would like to make the point that the New Delhi and Islamabad

dominated dialogue have failed to come up with any solution to vexed issues like Kashmir. Maybe sub-

regions like Punjab and other border provinces like Rajasthan-Sind which have positive vested interests

in the borders opening up can pressurize central governments to seriously examine the need for higher

levels of trade and sustained people to people interactions.

Over and above anything else, ever since the partition of 1947, there is a feeling that the Muslim-Non

Muslim rift is something indelible and permanent. If both the Punjabs can lead the way it would be

ironic that a region partitioned on the basis of religion acts the "peacemaker" utilizing amongst other

tools a common culture. But there is only a limited role which a common identity can play in bridging

the gaps.

Finally, members of the strategic community need to pay more serious attention to the fact that the

common Punjabi identity could be a useful way of countering the rising wave of fundamentalism

in Pakistani Punjab, which was earlier dominated by Sufi thought.

Courtesy: The Culture and Conflict Review (Naval Postgraduate School USA)

The Institute of Sikh Studies (IOSS), Chandigarh organized a public lecture on the topic: "Punjab:

Can It Be a Bridge to Peace Between India and Pakistan?" on 5th May 2012 at its headquarters at

Gurudwara Sri Guru Singh Sabha, Kanthala, Industrial Area, Phase 2, Chandigarh.

The Lecture was delivered by Mr. Tridivesh Singh Maini of The Observer Research Foundation,

New Delhi, who has authored a number of books on Indo-Pak relations. He felt that there was a

need to promote the common Punjabi identity without making it hostage to jingoistic nationalism.

Religious tourism, educational exchanges and trade have gone a long way in normalizing Indo-Pak

relations even when they had got strained post the Kargil war, the Mumbai terrorist attacks etc.

Such exchanges take the interaction between the nations to the grassroots level and there is a need

to further strengthen such exchanges. He also felt that collaborative efforts between the writers and

regional presspersons of both nations can go a long way in improving relations between both the

nations. Both the Punjab governments need to send recommendations to the Central Government to

liberalize visa regimes between the two countries to promote more such exchanges. He appreciated

the efforts of the Punjabi Diaspora of both countries who have been taking steps to improve Indo-Pak

relations even during times of strained relations between India and Pakistan and felt that they need

to be involved in any future efforts in this direction. He concluded by saying that there was a need to

blend emotions with reality while devising a structure for further improving Indo-Pak relations.

Dr Sardara Singh Johl, an eminent economist and former vice-chairman of the Planning Commission

of Punjab stressed on the importance of promoting common economic interests for improving relations

between both the nations. He highlighted areas like collaborative agricultural research, trade of citrus

fruits etc in which cooperation between India and Pakistan were possible. He also shared his personal

experiences of interaction with local people during his visits to Pakistan.

Dr G S Kalkat, Chairman Punjab State Farmers Commission explained that the economy of Punjab can

improve only if we have free trade with Pakistan. He informed the audience that other Indian states

like U.P., M.P. etc were now increasingly becoming self-sufficient in producing wheat and rice. Hence,

the farmers of Punjab have to diversify into growing vegetables and fruits and then export them in

frozen form to Iran and Central Asia via Pakistan.

Dr Kirpal Singh, an eminent Historian, shed light on the role of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in promoting

better relations between Sikhs and Muslims. He gave examples from his personal life to highlight the

profound respect which Muslims have for Sikhs.

Mr. P.S.Pruthi, Chief Commissioner of Customs & Excise highlighted the painfully slow progress in

economic integration between India and Pakistan. He explained that now-a-days products from distant

states like Maharashtra, M.P., Rajasthan etc were being exported to Pakistan via Attari border. However,

the state of Punjab was lagging behind in this respect.

Lt. Gen. (Retd.) Kartar Singh Gill shared his experiences from the 1965 and 1971 wars with Pakistan.

He explained that the elder generation of India and Pakistan had lived together before partition and

has a sense of shared heritage. The younger generation however is quite different because they have

grown up under the belief that the other side is their biggest enemy. Therefore, there is a dire need to

promote student exchanges so the younger generation can understand each other better and overcome

any jingoistic indoctrination.

Prof. Nirmal Singh (USA) stressed the importance of focusing our efforts in the right place. He felt that

one area where we need to focus our efforts is in educating the young Sikh kids in Pakistan. These

kids are the future of our community in Pakistan but have very little exposure to the outside world and

to proper education. Hence, it was incumbent upon the Sikh community to take steps towards ensuring

a bright future for these kids.

Earlier, Principal Prabhjot Kaur (IOSS President) welcomed the audience and briefly introduced the

speakers. She said that cordial Indo-Pak relations were very important for the Sikhs because only then

they can realize the desire for proper upkeep and management of Gurudwaras in Pakistan by themselves

which is expressed in their daily Ardas. Mr. Gurpreet Singh, treasurer of the IOSS was the stage secretary

of the event. Bhai Ashok Singh read out the resolution passed (given below) by the gathering and

delivered the vote of thanks on behalf of the IOSS.

Resolution

"Building up strong cultural and economic strength between India and Pakistan will be a positive exercise

to maintain peace towards this the extent of contribution which that Punjab can make was the subject of a

convention organized by the Institute of Sikh Studies. The august gathering demands from the Govt of

India that:

1. A common Agriculture Research Station should be established by both the countries

2. Interaction between students of Pakistani and Indian should be increased

3. Kartarpur Corridor be opened and

4. Visa centers at Lahore and Amritsar invariably be established.

To make this southern part of Asia a world power, it is essential that India and Pakistan develop peaceful

relations so that proper conditions are created for Punjab to contribution its possible might."

Send email to nazeerkahut@punjabics.com with questions, comment or suggestions

Punjabics is a literary, non-profit and non-Political, non-affiliated organization

Punjabics.com @ Copyright 2008 - 2018 Punjabics.Com All Rights Reserved

Website Design & SEO by Webpagetime.com